Columbus Museum of Art American Curator Melissa Wolfe tells the story of American Surrealism in conjunction with Modern Dialect: American Paintings from the John and Susan Horseman Collection, an exhibition now on view at CMA through August 31. Modern Dialect showcases American Modernist paintings from the 1920s to the beginning of World War II including work by artists showing a very American take on Surrealism.

(Above: Red Ventilator by Arthur Osver, John and Susan Horseman Collection).

The story of early twentieth-century American art has typically been told according to watershed moments—the buildup and aftershock of the 1908 exhibition of The Eight at MacBeth Galleries, the presentation of the Armory Show in 1913, and the innovations of the Abstract Expressionists at mid-century. Yet any narrative carries the risk of marginalizing certain interests and proclivities in its focus on the prevailing story of time and place. American Surrealism has often found itself relegated to this position, the coherence and dynamics of its story broken up to fit the shape of the accepted dominance of The Eight–Armory Show–Abstraction trajectory. However, American Surrealism developed out of a heady series of events in the art world that were just as significant, and just as cohesive, as The Eight and the Armory shows.

In November 1931 the Wadsworth Atheneum opened Newer Super-Realism (often called The New Super Realism), an exhibition of forty-nine paintings by leading European Surrealists including Salvador Dalí, Giorgio de Chirico, Max Ernst, André Masson, Joan Miró, and Pablo Picasso, among others. In January 1932, the majority of the works were again exhibited at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York. Together the shows commanded the rapt attention of the American art world, initiating a consistent and oft-debated presence for Surrealism over the course of the decade. The Levy Gallery showed work by Max Ernst again in 1932, and Dalí had his first U.S. solo exhibition there in 1934, the same year that the Pierre Matisse Gallery held Andre Masson’s first solo U.S. exhibition. Major museums joined in presenting Surrealism to the American public, as well as endowing it with institutional legitimacy. In 1936, Alfred Barr organized the massive Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism for the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), which included more than six hundred objects.

Surrealism provoked a broad spectrum of responses from the American population, as some found themselves drawn to its novelty and strangeness and others to its more serious theoretical underpinnings of revolt against rationality and conformity. The extremes of celebration and ridicule nearly matched that of the earlier unveiling of European avant-garde developments at the Armory Show. On one hand Dalí became the darling of American culture, with his portrait gracing the cover of Time magazine’s December 1936 issue; on the other hand, MoMA’s show that same year received a barrage of criticism from disgust to ridicule led by Art Digest’s December 15 headline, which jeered “Modern Museum a Psychopathic Ward as Surrealism Has Its Day.” Whether a subject of celebration or ridicule, Surrealism found itself in the national limelight throughout the decade.

For a number of significant reasons, American Surrealism of the 1930s took a slightly different turn from following in the footsteps of its European precursor. While the movement was introduced to the United States through work created by artists central to its formation in Europe six years earlier, the artists themselves rarely followed their works across the Atlantic until much later. Consequently, leaders such as André Breton held a less forceful control over the movement’s ideological and stylistic development among the Americans than he did among its European practitioners. Surrealism was somewhat diffused in the states, allowing American artists a certain freedom in its assimilation that likely would not have been possible had they been experimenting with the style in the presence of their European counterparts. Furthermore, the arts community experienced the two seminal Surrealism exhibitions in conjunction with several other influential artistic events that both enriched and complicated the direction that American artists associated with Surrealism ultimately chose. Before looking at the works created by American artists interested in Surrealism, however, it is informative to note the various complications that affected the coherence of the story, including experiences that influenced how these artists forged their particular understanding of the Surrealist style and ideas.

Among all the European Surrealists, the Spaniard Salvador Dalí, who was in many ways marginalized within the European group, most influenced the nature of the American practitioners throughout the 1930s. Both the Wadsworth and Levy Gallery shows included Dalí’s immediately famous work The Persistence of Memory, which Levy had purchased from the artist’s Paris gallery, Galerie Pierre Colle, earlier in 1931. The painting epitomizes the luminous surface finish, meticulous veristic detail, and juxtaposition of incongruous objects that proved most evocative to American artists. Consistently in the public eye throughout the 1930s and ’40s, Dalí had solo exhibitions at the Levy Gallery in 1933, ’34, ’36, ’39, and ’41, and he even relocated to the United States from 1940 to 1948, after having fled France during the Nazi invasion. From the time of his first visit in 1934, the artist’s extravagant theatrics—from lecturing while leading two Russian wolfhounds, a billiard cue in hand, and a diving helmet on his head (that nearly suffocated him) to showing up at a party given for him by New York’s social elite with a glass case on his chest that contained a brassiere—garnered the attention of the national media. Probably rather accurately, in 1937 the Art News stated that “To most Americans Dalí represents surrealism in all its horror and fascination.”

Yet Dalí was not the only artist from the Wadsworth and Levy shows who had a strong influence. The Italian metaphysical painter Giorgio de Chirico had also been included in the exhibitions, and had even been introduced to Americans earlier in a solo show at the Valentine Gallery in New York in 1927. His eerily brooding built environments, with their silent streets, stretching shadows, and sublimely skewed scale animate a work such as Gare Montparnasse (The Melancholy of Departure), which was shown at the Pierre Matisse Gallery during the 1930s. De Chirico’s works evoke the same uncanny and unnerving “mis-remembering” that haunts Dalí’s grotesque forms and empty landscapes. Many of the objects in the two artists’ works share an ambiguity of communication, such as the forms in the right foreground of de Chirico’s painting that seem to vacillate between the erotic and the repulsive.

The introduction of this brand of Surrealism collided in the United States with yet another innovation from Europe. In March and April of 1931, only months before the Atheneum and Julien Levy shows, MoMA exhibited German Painting and Sculpture, which included paintings by Max Beckmann, Otto Dix, and Georg Grosz in the style known as Neue Sachlichkeit, or New Objectivity. Dix’s Dr. Mayer-Hermann, which was included in the exhibition, exemplifies this style. Every little object has an intense, somehow overly factual veracity that, when mixed with the nearly satirical use of rotund forms around the hefty doctor, creates a disquieting anxiety. The Neue Sachlichkeit painters gave vent to the social anxieties of life in postwar Germany, and in this they offered American artists a visual language that helped them to manifest their own conflicted experiences of the 1930s, with its near devastation of economic and ecological systems and looming presence of fascism. If Dalí and de Chirico offered a language of personal anxiety, the Germans offered examples that broadened it to engage shared social anxieties as well.

The social content of such images found kinship in the controversial presence of the Mexican muralist then creating large public works that expressed social engagement in a passionate visual language. In the early years of the 1930s, José Orozco was painting his frescos at Dartmouth College in front of a rapt audience, and in 1933 Diego Rivera’s provocative murals in Rockefeller Center were unveiled and promptly destroyed, to much public ado. These images, such as Orozco’s Gods of the Modern World, offered even more heady material to American artists, with their fiery social messages conveyed through a Cubist-inspired conflation of form and content. In a protest against the worship of dead knowledge, Orozco depicts a skeletal obstetrician in an academic gown delivering yet more skeletons, stillborn, from a skeleton lying on a bed of books. Pushed out into our space by the garish red of lurid flames, the angular, rigid forms of the operation and its professorial audience spill out toward us like objects packed too tightly within accordion folds.

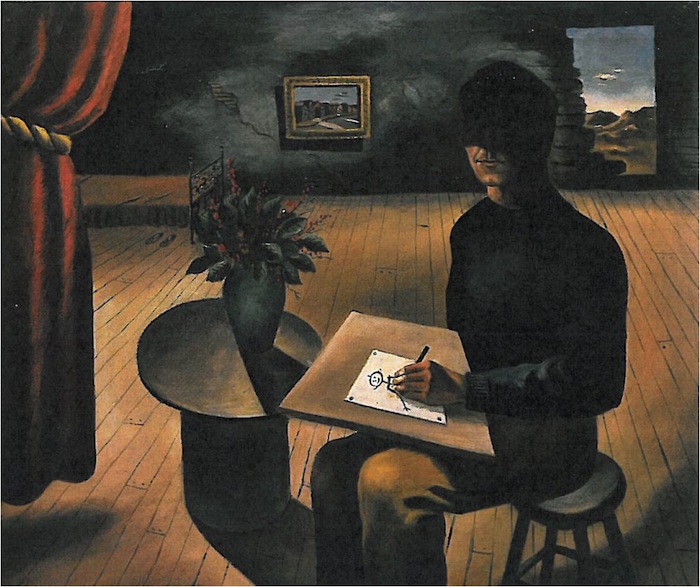

Untitled by John Wilde, 1941, John and Susan Horseman Collection

As these works by Dalí, de Chirico, Dix, and Orozco suggest, in just five short years American artists (and their public) experienced not only an impressive introduction to the European Surrealists mostly centered in Paris, but also a flood of dramatic visual strategies that fed the Surrealist language that American artists could use to express the complicated experiences of modern life. Generally unencumbered by any single source, American artists freely mixed these strategies to find their own effective modes of expression. While at times an artist embraced the styles and concepts of certain artists or movements, more often American artists preferred to use and combine elements to express their particular interests and concerns. The nature and variety of their choices can be found in the works presented in Modern Dialect.

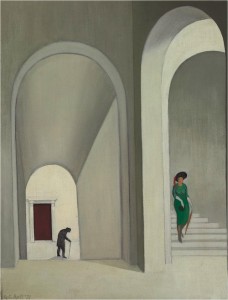

Night Arrives by Gertrude Abercrombie, 1948, John and Susan Horseman Collection

Dalí’s use of juxtaposition—among the most striking ways he influenced American artists—expressed the associations of objects, memories, dreams, and other experiences in our internal world that repudiate, or, at best, do not align with the rules of rationality that we assume govern our world. Artists whose works are featured in Modern Dialect, such as Gertrude Abercrombie (pictured above), James Noecker (pictured below), and John Wilde (above) created enigmatic, inexplicable scenes that nonetheless are acutely evocative. Like Dalí, whose profile lurks in the erotic folds of the tongue form that drapes across the center of his composition, all three of these American artists include representations of themselves, though none provide a direct exchange with the viewer. Their figural inclusion indicates their ownership of the logic that determines the objects, actions, and space of the painted world they create and inhabit. The inclusion of the artist also asserts an invitation, of sorts, to the viewer to wander unaided through the space of the painting, whose meaning is nonetheless only fully available to its host. In Abercrombie’s Night Arrives, the association of whales, the sea, somnambulists, masks, and the moon seem psychoanalytically related, to have a deep and compelling connection, yet that connection is a mysterious one and oddly intent on its own disavowal. The objects seem flatly what they are, as they are, and nothing more. They are there simply because they have been put there—and that should be enough.

The Genius? by James Harold Noecker, 1942-3, John and Susan Horseman Collection

In works such as The Stairway by George Ault, the narrative hinges on a juxtaposition that is not explicitly a Surrealist one (such as Dalí’s), but a combination more closely related to that silent alienation associated with de Chirico. And, indeed, de Chirico left a powerful mark on American artists, if a less sensational one than Dalí’s in its presentation. The isolation that the built environment creates for the two figures who wander Ault’s spaces seems to suggest that they exist in separate realms, never to meet; each will just pass out of the other’s view as they turn their respective corners. Juxtaposing the two figures, the painting forever suspends them, visually, in that prevenient moment upon which the frustrating definition of “almost” hinges. The temporal slippage between events causes two entities to miss sharing a convergent moment in time and space. Its visualization here is, in essence, the visualization of what is forever to have been lost, of showing what is forever to have not happened. In a decade defined by profound social and political instability, American artists understandably responded powerfully to de Chirico’s “mis-moments,” which gave a visual outlet to the era’s frustrating suspension of desire, rather than its resolution.

One group of artists who drew readily from Surrealism were those who found in it a way to convey their anger and dismay over the social and political conditions of the United States in the 1930s. Social Realism, a style used to engage viewers in social change, was a major force in the art world, and James Guy, one of its practitioners, was an activist throughout the decade. He helped to produce a labor play titled Strike in Provincetown; he was a member of the John Reed Club, a Communist-associated cultural organization; and he had painted a mural for the 13th Street Communist Worker’s School. Early in his career he had seen the Surrealist show at the Atheneum, and had traveled to Dartmouth to watch Orozco working on his murals. Like several others, especially his close friend the painter Walter Quirt, he employed the Surrealist device of juxtaposing incongruous images to convey psychological meaning to suggest instead social and political meaning.

In On the Waterfront, Guy counters a lean striker with his enlarged fist clenched, as well as a boss and a policeman who brandishes a billy club. In a hollow building that casts an ominous shadow onto the street, a politician stands with his back to a pile of skulls as he relieves Uncle Sam of his money and takes the tickets of the wealthy who prepare to board a liner docked on a calm sea. Behind the striker, the sea is inexplicably in the throes of a tempest so great it has capsized a ship, forcing its passengers to fend for themselves in the water. The warning that the coming storm raging in the space of the striking worker will soon descend on the space of the unsuspecting privileged is told through the close juxtaposition of narrative and symbolic elements. This Surrealist approach began to gain the attention of critics, who commented that “It is evident that the social content artists have been making headway . . . in their endeavor to . . . express with dramatic power the social ideas and social movements of our time. In this endeavor they have been helped to a certain extent by Surrealist methods of daring and fantastic juxtapositions which reveal the unfamiliar, the strange, and the disturbing in the recesses of familiar fact.”

On the Waterfront by James Guy, 1937, John and Susan Horseman Collection

While these American artists employed quite explicit techniques and styles from the Surrealist examples they encountered in the 1930s, perhaps Surrealism’s most lasting influence on American art can be seen in the work by artists who absorbed elements of the style less explicitly. The art of the 1930s has a noticeable proclivity to contain a bit too much expression, to be a bit baroque. Much art that is readily characterized (and often too readily dismissed) as American Scene with no further aim than a simple realism seems to contain a little too much emotional content than is necessary to convey its narrative or setting. There is a subtle excess in these works that, while persistent, does not insistent on its acknowledgement by the viewer. Its presence is sometimes best realized when considered in the context of more explicitly Surrealist compositions.

For instance, de Chirico’s influence can be felt in the powerful force that animates the inanimate in Arthur Osver’s Red Ventilator. The monstrous scale of the machine dwarfs the worker at its side. Its disquietingly hollow Cyclops eye seems to impel stiff tentacles to break from their rickety scaffolds, lurching toward some unknown distant object of immense desire. Such an unequivocal Surrealist reading informs a response to Lloyd Goff’s Thanksgiving Day Parade. Goff’s work depicts a communal scene straight from the American Scene roster—a recognizable bend in New York’s venerable parade. The painting can be read as just exactly this. However, a perceptible disparity of scale and weight exists between the monstrous, looming balloons and the crowds in their paths. Once recognized, the disparity becomes more noticeably excessive, and in some darkly humorous mode takes on the nature of a perverse Godzilla-like movie in which the brightly colored bulbous characters float ominously over crowds that huddle with some uncertainty in the long shadows. Or, while there is nothing out of the ordinary in John Rogers Cox’s painting Wheat Field, there is a pervasive, and undeniable, sense of suspension, of hovering, in the unspoken relationship among the cloud, its shadow, and the golden wheat below.

Sometimes this underlying sense of unease seems to be a result of too much seeing, on the part of both viewer and artist. Helen Lundeberg was a founding member of the only formally organized Surrealist group in the country. Calling themselves the Post-Surrealists, the West Coast group created highly deliberate compositions that manifest the artists’ metaphysical ideas through highly controlled symbolic content and juxtaposition. Lundeberg described her approach as a type of classicism in its dependence on a calculated, intensely considered relationship between all the compositional elements to create the effect of the whole.[4] Iris presents its subject with meticulous care, with an intensity of observation that recalls the overly studied objects of Neue Sachlichkeit works, and that begins to suggest a trompe l’oeil so effective that it moves the object into a kind of super-realism—an object that contains an excess of animate presence. Again, this effect often seems unintentional on the part of the artist, but rather is an unconscious manifestation of the country’s profound unease. Similarly, Zoltan Sepeshy’s work Driftwood (The Dying Tree) is one of many works by the artist that depicts the sand dunes near Frankfort, the Lake Michigan fishing town where he had a summer home. However unintentionally, the driftwood seems so over-realized that its bleached and desiccated form becomes animate, revealing an otherwise latent primordial nature.

Zoltan Sepeshy’s Driftwood (The Dying Tree) from the John and Susan Horseman Collection

Interestingly, Clarence Carter places this mystical and disorienting act of intense seeing within his composition. The women in Down the River stand on the floodwall along the Ohio River at Carter’s hometown of Portsmouth, Ohio. In January 1937, the year the work was painted, the Ohio River flooded, killing more than 375 people and destroying over a million homes. Scenes of ecological disaster were a dominant theme for American Scene painters, such as John Steuart Curry’s painting Mississippi of 1935, which recalls the great Mississippi flood of 1927. However, the psychological differences between Carter’s work and more typical American Scene disaster subjects becomes clear in its comparison to Curry. The explicit narrative and thematic content of Curry is direct and intentionally legible, while Carter’s work is oddly split. The two women are monumentalized, oversized in comparison to the river scene they observe below. The story of the flood is not told through them directly, as they turn their shrouded backs to the viewer, effectively both blocking our direct view of the subject and refusing to tell us what they see. The women are seers who take in what we cannot, visually and, importantly, psychologically. The immensity of the disaster, conveyed through both their refusal and their silence, leaves us to piece together the disparate ideas in our imagination to construct the view ourselves, to construct within ourselves in Surrealist fashion this tragic scene. The work is not explicitly Surrealist but rather implicitly and, importantly, self-consciously so.

Clarence Carter’s Down the River, from the John and Susan Horseman Collection

In such works, American artists did not simply adopt the ideas and strategies of the various imports of Surrealism, nor did they facilely combine them. Rather, at their best, as exemplified by Carter’s beckoning and yet stubborn creation, American artists absorbed Surrealist ideas and techniques, creating out of a barrage of disparate visual material, a form and content that resonated and in important ways defined the anxieties and experiences of their time and place.

Modern Dialect: American Paintings from the John and Susan Horseman Collection will remain on view at Columbus Museum of Art through August 31, 2014.

(From American Surrealism, (non)Sense and Sensibility: Surrealism in 1930s America by CMA Curator Melissa Wolfe, excerpted from the Modern Dialect catalogue).