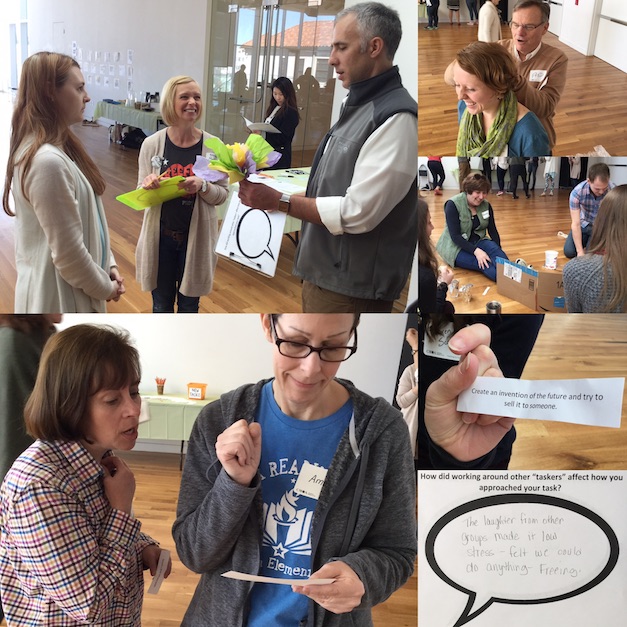

Teachers practicing their own creativity at the final workshop of the Teaching for Creativity Institute.

Recently I had an experience that left my head swimming. It was the last session of the Teaching for Creativity Institute , and we were closing out the year with a day of teacher-led workshops. The participants in the Institute and the Leaders for Creativity fellows who designed the day are extraordinary. I have worked with them in different ways all year long, and seen them re-imagine, experiment, and reflect in truly impressive ways. It isn’t surprising, then, that I walked away from this bonanza of puzzles and inspirations with many ideas bouncing around in my mind, ricocheting off one another to head off in new directions.

One such sticky idea came from Jason Blair, a teacher and frequent thought partner. He highlighted creativity as a mindset with us all the time – not a behavior confined to particular moments and packed away when it is time to move on to more serious pursuits. Learning can be designed to explicitly build and stretch creativity; however, if we really value creativity we must celebrate it all the time.

This sounds simple at first. Who wouldn’t want to support creativity all the time? In practice, though, we often welcome creativity only when it is on our terms.

Jason contrasted the reaction to student creativity on an assigned project – This is exactly what I hoped for! – to the reaction when a child demonstrates creativity when it hasn’t been asked for, like dancing down the hall rather than walking – That is NOT the way we behave in the hallway! Show some maturity! We adults, after all, know better. There is time for imagination and play, but it had better respect the schedule.

You may be thinking that rules are in place for safety; just one false dance move can land a kid in the nurse’s office. That is a fair point, and at the Museum we take the safety of visitors and art very seriously. But reflecting on every moment as a space for creativity, how might we maintain safety while fostering imagination, another priority during a museum visit? Cat Lynch, who leads young child programming, has some delightful approaches to this. For example, she might have children imagine sneaking through the jungle of a landscape (“remember to quietly push aside the vines and grasses!”), or imagine they are creatures, characters, or crew-mates of a vehicle in a work of art they have just explored together, (“we’ll need to steer together”).

Cat also has a rule in her summer programs that any play fighting must be done in slow-motion. Kids of all ages love to play-fight, but this presents a threat to safety. Instead of engaging in an unwinnable fight against fighting, Cat identified the actual reason fighting is a bad idea, and found a creative compromise. The result is as absurd as you are probably imagining – but no one gets hurt, and there is the bonus benefit that kids have an understanding of why they shouldn’t play fight (i.e. even if it is a game to you, quick and violent motions could hurt someone.) This is just one educator’s response to the specific example of walking down the hall, but it illustrates that we can identify what matters about a rule and find ways to get what we need without inhibiting creativity.

When we stifle creativity that emerges organically at a time that is “inconvenient” for us, we make spaces unsafe for originality. When we value conformity and obedience in children, we crush the impulses needed for creativity, the basis of change and innovation. Later, as these young people enter the workforce, we wonder what happened to their creativity problem solving skills. Perhaps we left them in that hallway.

Innovators don’t spend their PreK-12 years assiduously following rules, then, upon receiving their exit ticket from high school immediately have the capacity to see the world in new ways. They were often the misfits all along. What we label rule-breaking in children, we often celebrate as visionary with adults. This, however, calls for a moment of honesty: We may value rebelliousness in the heroic stories of innovators, but how often do we really value and cultivate radically original ideas in our own workplaces? If you want a deep-dive into this, I recommend Originals: How Non-Conformists Move the World by Adam Grant. It is a must-read for anyone who cares about fostering better ideas in their organization. CMA just wrapped a Leadership Series group-read of Originals in partnership with the Martha Holden Jennings Foundation. The book upends a lot of assumptions and workplace practices, and left me with many puzzles and knots to tease out when I reflect on my own management practice.

As managers and colleagues are we welcoming and rewarding creativity, even when it’s not “on our terms?” Or do we shoo it off in order to “get down to business?” In thinking about “safety” (physical or otherwise), do we set and communicate intentional parameters so that our teams can be free to imagine? Anyone who wants original ideas must be willing to look long, hard, and often at what they should start doing, stop doing, and do differently in order for creativity to thrive on its own terms.

You can follow Jason Blair on Twitter @epesArt for more of his insights into creativity in learning

Find out more about the next Creativity Institute. Final deadline to apply is May 5, 2017.

The Teaching for Creativity Institute and the Leaders for Creativity Fellowship are supported by the Martha Holden Jennings Foundation.

-Jennifer Lehe, Columbus Museum of Art Manager of Strategic Partnerships