History-mapping draws the wide and narrow, the known and unknown past to the present. During my residency at the Aminah Robinson house, I examined the impulses behind my prose poem “Blood on a Blackberry” and found a kinship with the textile artist and writer who made her home a creative safe space. I crafted narratives through a mixed media application of vintage buttons, antique laces and fabrics, and text on cloth-like paper. The starting point for “Blood on a Blackberry” and the writing during this project was a photograph taken more than a century ago that I found in a family album. Three generations of ancestral mothers held their bodies still outside of what looked like a poorly-built cabin. What struck me was their gaze.

Three generations of women in Virginia. Photograph from the writer’s family album. Museum art talk “Time and Reflection: Behind Her Gaze.”

What thoughts hid behind their deep penetrating looks? Their bodies suggested a permanence in the Virginia landscape around them. I knew the names of the ancestor mothers, but I knew little of their lives. What were their secrets? What songs did they sing? What desires sat in their hearts? Stirred their hearts? What were the night sounds and day sounds they heard? I wanted to know their thoughts about the world around them. What frightened them? How did they talk when sitting with friends? What did they confess? How did they talk to strangers? What did they conceal? What was girlhood like? Womanhood? These questions led me to writing that explored how they must have felt.

Research was not enough to bring them to me. Recorded public history often distorted or omitted the stories of these women, so my history-mapping relied on memories associated with feelings. Toni Morrison called memory “the deliberate act of remembering, a form of willed creation – to dwell on the way it appeared and why it appeared in a particular way.” The act of remembering through poetic language and collage helped me to better understand these ancestor mothers and give them their say.

Photographs of the artist and visual texts of ancestor mothers hanging in studio at Aminah Robinson house.

Working in Aminah Robinson’s studio, I traveled the line that carries my family history and my creative writing crossed new boundaries. The texts I created reimagined “Blood on a Blackberry” in hand-cut shapes drawn from traditions of Black women’s stitchwork. As I cut excerpts from my prose and poetry in sheets of mulberry paper, I assembled fragmented memories and reframed unrecorded history into visual narratives. Color and texture marked childhood innocence, female vulnerability, and bits of memories.

The blackberry in my storytelling became a metaphor for Black life constructed from the poetry of my mother’s speech, a southern poetics as she recalled the ingredients of a recipe. As she reminisced about baking, I recalled weekends gathering berries in patches along country roads, the labor of children collecting berries, placing them in buckets, walking along roads fearful of snakes, listening to what might be ahead or hidden in the bushes and bramble. Those memories of blackberry cobbler suggested the handwork, craftwork, and lovework Black families lean on to survive struggle and celebrate life.

In a museum talk on July 24, 2022, I related my creative experiences during the residency and shared how questions about ancestors infused my storytelling. The Blood on a Blackberry collection exhibited at the museum expressed the expansion of my writing into multidisciplinary form. The layers of collage, silhouette, and stitched patterns in “Blood on a Blackberry,” “Blackberry Cobbler,” “Braids,” “Can’t See the Road Ahead,” “Sit Side Me,” “Behind Her Gaze,” “Fannie,” “1870 Census,” and “1880 Census” confronted the past and imagined memories. The final panels in the exhibit introduced my tribute to Fannie, born in 1840, a likely enslaved foremother. While her lifetime rooted my maternal line in Caroline County, Virginia, research revealed sparse lines of biography. I faced a missing page in history.

Photograph of artist’s gallery talk and discussion of “Fannie,” “1870 Census,” and “1880 Census.”

Aminah Robinson understood the toil of reconstructing what she called the “missing pages of American history.” Using stitchwork, drawing, and painting she re-membered the past, preserved marginalized voices, and documented history. She marked historical moments relating life moments of the Black community she lived in and loved. Her work talked back to the erasures of history. Thus, the house at 791 Sunbury Road, its contents, and Robinson’s visual storytelling held special meaning as I worked there.

I wrote “Sit Side Me” during quiet hours of reflection. The days after the incidents in “Blood on a Blackberry” required the grandmother and Sweet Child to sit and gather their strength. The start of their conversation came to me as poetry and collage. Their story has not ended; there is more to know and claim and imagine.

Photograph of artist cutting “Sit Side Me” in studio.

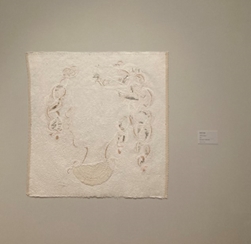

Photograph of “Sit Side Me” in the museum gallery. Image courtesy of Steve Harrison.

Sit Side Me

By Darlene Taylor

Tasting the purple-black spoon against a bowl mouth,

oven heat sweating sweet nutmeg black,

she halts her kitchen baking.

Sit side me, she says.

I want to sit in her lap, my chin on her shoulder.

Her warm, dark eyes cloud. She leans forward

close enough that I can follow her gaze.

There’s much to do, she says,

placing paper and pencil on the table.

Write this.

Somewhere out the window a bird whistles.

She catches its voice and shapes the high and low

into words to explain the wrongness and lostness

that took me from school. A girl was snatched.

She remember the ruined slip, torn book pages,

and the flattened patch.

The words in my hands scratch.

The paper is too short, and I can’t write.

The thick bramble and thorns make my hands still.

She takes the memory and it belong to her.

Her eyes my eyes, her skin my skin.

She know the ache as it passed from me to her,

she know it like sin staining generations,

repeating, remembering, repeating, remembering.

Remembering like she know what it feel like to be a girl,

her fingers slide across the vinyl table surface to the paper.

Why stop writing? But I don’t answer.

And she don’t make me. Instead, she leads me

down her memory of being a girl.

When she was a girl, there was no school,

no books, no letter writing.

Just thick patches of green and dusty red clay road.

We take to the only road. She looks much taller

with her hair braided against the sky.

Take my hand, sweet child.

Together we make this walk, hold this old road.

A milky sky flattens and eats steam. Clouds spittle and bend long the road.

Photographs of cut and collage on banners as they hang in the studio at the Aminah Robinson house.

Blood on a Blackberry

By Darlene Taylor

The road bends. In a place where a girl was snatched, no one says her name. They talk about the

bloody slip, not the lost girl. The blacktop road curves there and drops. Can’t see what’s ahead

so, I listen. Insects scratch their legs and wind their wings above their backs. The road sounds

safe.

Every day I walk alone on the schoolhouse road, keeping my eyes on where I’m going,

not where I been. Bruises on my shoulder from carrying books and notebooks, pencils and

crayons.

Pebbles crunch. An engine grinds, brakes screech. I step into a cloud of pink dust and weeds.

The sandy taste of road dust dries my tongue. Older boys, mean boys, cursing beer-drunk boys

laugh and bluster—“Rusty Girl.” They drive fast. Their laughs fade. Feathers of a bent bluebird impale the road. Sun beats the crushed bird.

Cutting through the tall, tall grass, I pick up a stick to warn. Songs and sticks have power over

snakes. Bramble snaps. Wild berries squish under my feet. The ripe scent makes my belly

grumble. Briar thorns prick my skin, making my fingertips bleed. Plucking handfuls, I eat.

Blood on a blackberry ruins the taste.

Books spill. Backwards I fall. Pages tear. Lessons brown like sugar, cinnamon,

nutmeg. Blackberry stain. Thistles and nettles grate my legs and thighs. Coarse

laughter, not from inside me. A boy, a laughing boy, a mean boy. Berry black stains my

dress. I run. Home.

The sun burns through kitchen windows, warming, baking. I roll my purple-tipped fingers into

my palms.

Sweet child, grandmother will say. Smart girl.

Tomorrow. On the schoolhouse road.

Photographs of artist cutting text and discussing multidisciplinary writing.