We got a grant, we got a grant! Thank you to Bank of America, who awarded the Museum support for conservation work on a selection from our collection of over 4,000 prints. It was an international competition, so you can all be very proud of us. We are.

It’s tough to choose which prints get treatment, especially with so many to sort through. Curators and Registrars work together. Curators think about the object’s significance in art history and the role it can play on display. Registrars know which prints need help due to tears, acidic mats, or age staining.

We used our partnership with the Dordrecht Museum and the Life in the Age of Rembrandt exhibition as a starting place. How many European prints did we have that were created before 1800? How many of those were by Dutch, Flemish, or Germanic artists? Between us, white-gloved and earnest, we chose 50 Old Master European prints. The youngest print is about 200-years-old. The oldest print is more than 500-years-old. We want them all to make it another 500 years at least.

We don’t have a conservator on staff, so CMA works with different ones according to our needs. In this case, we went to Gina McKay, a paper conservator at McKay Lodge Conservation located in a farmhouse compound outside Oberlin, Ohio. At last count they had 7 dogs. At least.

Gina and her folks looked at every print, measured it, photographed it, and gave a summary of its condition and estimated cost to repair. Some things just needed better mats. Some required more aggressive treatment, such as bathing to remove stains. While putting paper in water makes us uninitiated people cringe, it’s something paper conservators do without much batting of eyes.

A good conservator doesn’t just think about what the work should look like ideally, but what they can do that is safe and won’t make the next generation of conservators shake their heads sadly. New hinges (the pieces of paper attached to the print so it can be attached to a mat so it can be framed and displayed) are easily reversible. Nothing is glued down permanently anymore.

One of the highlights of the project was seeing the finished Albrecht Dürer print. The conservators, who are supposed to be used to this sort of thing, were so excited to show us how it came out that they unwrapped it for us. We all gathered around the conservator’s microscope in awe.

I am constantly surprised by what can come to life beneath the fingers of a master printmaker. They coax texture, shading, and the curve of a human figure from a plate of metal or wood. A simple inventory sometimes goes quite slowly because we can’t help stopping to admire the techniques.

It’s intensely satisfying for Museum folk to be able to assure that a work of art will last from this generation to the next and the next.

Come see the results for yourself. The new restored prints are on view now in Gallery 5.

(Video courtesy of WOSU).

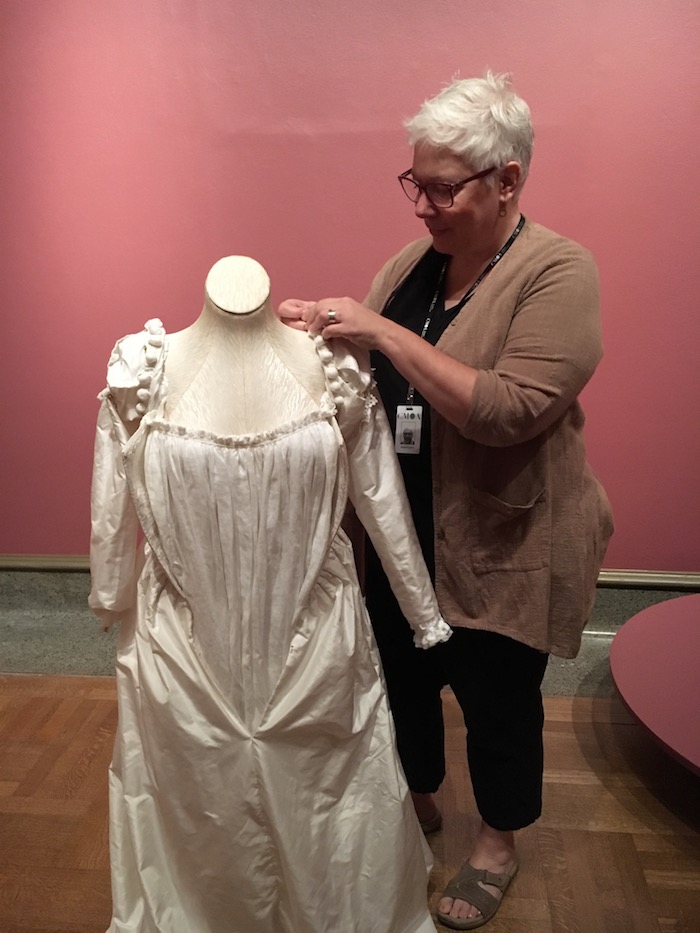

- Elizabeth Hopkin is Associate Registrar at Columbus Museum of Art, and has also been designing and building costumes for ballet and theatre in Central Ohio for more than 14 years. She has worked on projects with Opera Columbus, Ballet Met, and is resident costume designer for Columbus Dance Theatre where she designed the costumes for the ballet Claudel, which won the Greater Columbus Arts Council award for Artistic Excellence.