Art After Stonewall, 1969-1989

Art after Stonewall, 1969-1989 is the first major exhibition to examine the impact on visual culture of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) liberation movement sparked fifty years ago with the Stonewall Uprising. The exhibition encompasses the two crucial decades after the Stonewall riots of June 1969, exploring the many ways artists across the United States — including those who identified as straight — responded to the movement’s call for queer visibility and self-expression.

There were no plans for rebellion in the early moving of June 28, 1969. It all began with a routine police raid on the Stonewall Inn, a Mafia-run gay bar in New York City’s Greenwich Village. The police expected to line up an acquiescent group of homosexuals, but instead encountered fierce resistance from the bar’s patrons. Among the group at Stonewall that night were the transgender activist Marsha P. Johnson and the gay artist Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt, who affectionately described his fellow resisters as “street rats.” Their collective refusal of police harassment marked what historian Martin Duberman has called “the birth of the modern gay and lesbian political movement.”

The years following the Stonewall Uprising saw the proliferation of gay, lesbian, and trans rights struggles across the United States, accompanied by joyous, transgressive cultural and artistic experimentation. Nevertheless, while the Stonewall riots marked a turning point in queer civil rights, a decade later the struggle for liberation was facing extreme backlash, as seen in the assassination of gay city supervisor Harvey Milk in San Francisco in 1979. There was also tension within the LGBTQ movement, which was not immune from perpetuating sexism, racism, and transphobia. With the outbreak of HIV/AIDS in the 1980s, the movement rallied to provide comfort and care to friends and lovers, while decrying the fatal inaction of the political establishment. Here are the six major themes of the exhibition.

COMING OUT

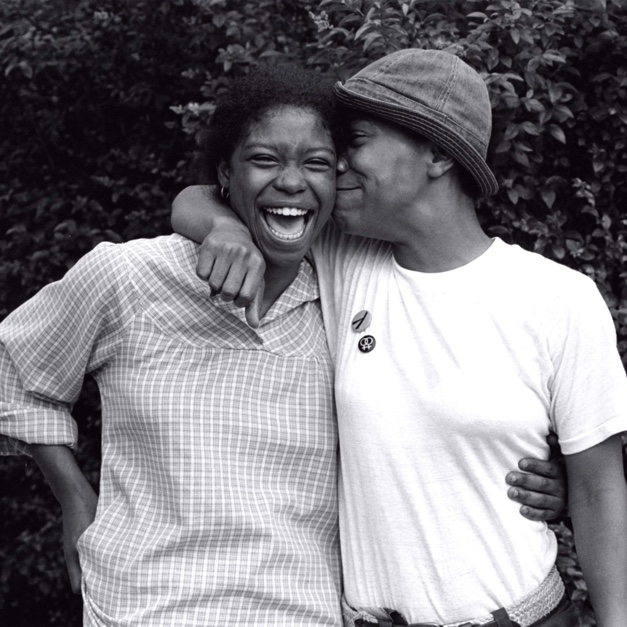

The call for LGBTQ people to publicly declare their identities has been a central feature of queer activism throughout the twentieth century. In the pre-Stonewall era, “coming out” did not mean announcing one’s homosexuality to straights, but often meant discretely participating in communal gay and lesbian life. In the aftermath of the Stonewall Uprising, “coming out” came to mean something radically different—to leave behind the oppressive closet of secrecy and repression, proudly acknowledging one’s identity with family, friends, and a wider public.

The call for LGBTQ people to publicly declare their identities has been a central feature of queer activism throughout the twentieth century. In the pre-Stonewall era, “coming out” did not mean announcing one’s homosexuality to straights, but often meant discretely participating in communal gay and lesbian life. In the aftermath of the Stonewall Uprising, “coming out” came to mean something radically different—to leave behind the oppressive closet of secrecy and repression, proudly acknowledging one’s identity with family, friends, and a wider public.

The works in this section emphasize how even small acts of visibility, such as holding hands or publicly kissing, can have powerful political repercussions. Launched in 1970 to commemorate the Stonewall Uprising, the first Gay Pride marches brought queers out of darkness and into the sunlight—acts of public self-identifications that inspired many more people to come out of the closet and into the streets.

It is important to remember, however, that the notion of “coming out” is based upon an idea of personal agency that assumes a level of privilege. Some people may choose to remain in the closet for reasons of safety or economic security, while for others who do not pass as straight or cisgender, there may not be a choice. For many trans folks, disclosing their gender histories may not feel liberating at all. In the 1970s and ’80s, there was often a high price to pay for being openly queer; countless people lost their families, children, homes, and jobs, risking personal safety simply for living their truth. Unfortunately, this still remains true today.

SEXUAL OUTLAWS

The rebellion sparked at the Stonewall Inn was more than a fight for equality. Energized by the sexual revolution of the 1960s, many LGBTQ people felt that the stifling norms of social conformity, and particularly the ways in which sexuality and gender identity were defined and policed, had to be radically challenged. It is worth remembering that in the year 1969, across most of the United States, homosexual and gender-nonconforming acts were still illegal, whether in bars and nightclubs or in the privacy of one’s own bedroom. For some artists, being marked as a sexual criminal bore a painful stigma, but for others, this stigma was worn as a badge of honor, defying the codes of censorship and decorum. Many of the works included in this section provoke strong and visceral responses—not simply as a shock tactic, but as a knock against the repressive systems that govern sexual behavior.

The rebellion sparked at the Stonewall Inn was more than a fight for equality. Energized by the sexual revolution of the 1960s, many LGBTQ people felt that the stifling norms of social conformity, and particularly the ways in which sexuality and gender identity were defined and policed, had to be radically challenged. It is worth remembering that in the year 1969, across most of the United States, homosexual and gender-nonconforming acts were still illegal, whether in bars and nightclubs or in the privacy of one’s own bedroom. For some artists, being marked as a sexual criminal bore a painful stigma, but for others, this stigma was worn as a badge of honor, defying the codes of censorship and decorum. Many of the works included in this section provoke strong and visceral responses—not simply as a shock tactic, but as a knock against the repressive systems that govern sexual behavior.

USES OF THE EROTIC

In her 1978 essay “The Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” Audre Lorde presented eroticism as a powerful source of female energy that can fuel personal growth and creative collaborations alike. The erotic is part of our sexuality, Lorde argues, but also a vital source for a politics of liberation, informing the ways we might move through life with passion and conviction: “There is, for me, no difference between writing a good poem and moving into the sunlight against the body of a woman I love.”

In her 1978 essay “The Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” Audre Lorde presented eroticism as a powerful source of female energy that can fuel personal growth and creative collaborations alike. The erotic is part of our sexuality, Lorde argues, but also a vital source for a politics of liberation, informing the ways we might move through life with passion and conviction: “There is, for me, no difference between writing a good poem and moving into the sunlight against the body of a woman I love.”

Underlying Lorde’s spiritual and political treatise is a hedonistic current—a celebration of physicality and queer desire. Art after Stonewall expands Lorde’s concept of the female erotic to think about the ways queer artists of all genders tap desire as a rich source of creativity.

While Lorde’s essay distinguishes between the pornographic and the erotic, such categories and hierarchies are continually challenged in queer art. Certainly, works by Alvin Baltrop or Robert Mapplethorpe were meant to be sexy, and key lesbian photographers at the time, including Tee A. Corinne and Morgan Gwenwald, published in erotic books and lesbian pornography magazines. However, the power of their images is not limited to their ability to arouse, but also lies in their potential to offer alternative ways of making physical, social, and spiritual connections.

GENDER PLAY

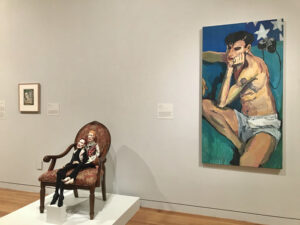

Cross-dressing and gender bending permeates the art of the 1970s and ’80s, from Vito Acconci’s Conversions, a video in which the artist attempts to squeeze his chest to form breasts, to Adrian Piper’s creation of a male alter ego in her Mythic Being project, to Charles Ludlam’s performances with the Ridiculous Theatrical Company. In a world where identities and sexualities were becoming more fluid and mutable, the ways artists presented and played with gender did not necessarily reflect how they personally identified, whether as straight or gay, cis or trans, femme or butch. The polymorphous identities and communalist ethos of the Cockettes projected a vision a of non-binary utopia of glitter and glam, while Phranc’s Jeanne Córdova doll set suggests how the gender politics of a “well-dressed dyke” might be put on and taken off like pieces of clothing.

Cross-dressing and gender bending permeates the art of the 1970s and ’80s, from Vito Acconci’s Conversions, a video in which the artist attempts to squeeze his chest to form breasts, to Adrian Piper’s creation of a male alter ego in her Mythic Being project, to Charles Ludlam’s performances with the Ridiculous Theatrical Company. In a world where identities and sexualities were becoming more fluid and mutable, the ways artists presented and played with gender did not necessarily reflect how they personally identified, whether as straight or gay, cis or trans, femme or butch. The polymorphous identities and communalist ethos of the Cockettes projected a vision a of non-binary utopia of glitter and glam, while Phranc’s Jeanne Córdova doll set suggests how the gender politics of a “well-dressed dyke” might be put on and taken off like pieces of clothing.

THINGS ARE QUEER

If a major focus of the LGBTQ movement in the wake of the Stonewall Uprising was the exhortation to “come out”—affirming one’s identity as gay, lesbian, or bisexual—the next generation of queer artists and activists took an increasingly critical view of these categories and of the systems of knowledge through which all identities are constructed. In the late 1970s, the word “queer,” originally coined as a slur for homosexuals, was reclaimed as a way of resisting social and sexual categorizations, including erotic practices and gender identifications falling between and outside those terms. Built into the word is an emphasis on difference and non-normative behavior. “Queer” defies categorization, since no one and nothing can be queer in quite the same way. In 1980, the artist David McDermott of the duo McDermott & McGough embraced the term, writing in the East Village Eye newspaper that “no one cares whether you are Gay or not, we care about who you are.”

If a major focus of the LGBTQ movement in the wake of the Stonewall Uprising was the exhortation to “come out”—affirming one’s identity as gay, lesbian, or bisexual—the next generation of queer artists and activists took an increasingly critical view of these categories and of the systems of knowledge through which all identities are constructed. In the late 1970s, the word “queer,” originally coined as a slur for homosexuals, was reclaimed as a way of resisting social and sexual categorizations, including erotic practices and gender identifications falling between and outside those terms. Built into the word is an emphasis on difference and non-normative behavior. “Queer” defies categorization, since no one and nothing can be queer in quite the same way. In 1980, the artist David McDermott of the duo McDermott & McGough embraced the term, writing in the East Village Eye newspaper that “no one cares whether you are Gay or not, we care about who you are.”

AIDS AND ACTIVISM

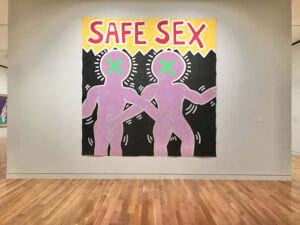

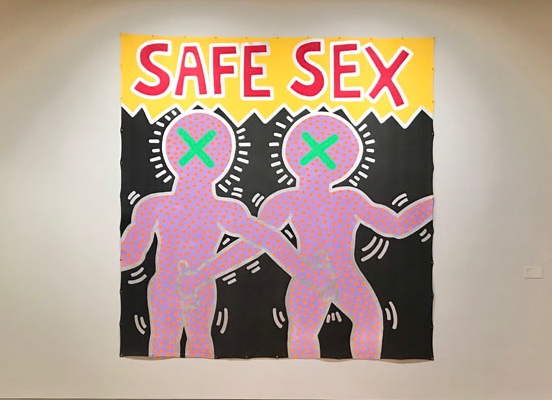

Ten years after Stonewall, as queer artists were exulting in their newfound freedom, the AIDS epidemic challenged the LGBTQ community to fight for their lives. HIV/AIDS devastated an entire generation, including many of the artists whose work is included in this exhibition. Echoing the apathy and homophobia of the Reagan and Bush administrations, the mainstream art world was initially slow to respond to the crisis, even as many artists were sick and dying. Working within and alongside activist organizations, including Gay Men’s Health Crisis, ACT UP, and Blood Sisters, artists raised public awareness about HIV/AIDS through propaganda campaigns and public interventions, yielding some of the most iconic images and slogans of 1980s queer rebellion—including SILENCE=DEATH. Drawing on the legacy of militant protest and coalition-building that flourished during and after the Stonewall Uprising, the artist-activists of the 1980s revived the struggle for social equality, justice, and queer lives—a struggle that still continues today.

Ten years after Stonewall, as queer artists were exulting in their newfound freedom, the AIDS epidemic challenged the LGBTQ community to fight for their lives. HIV/AIDS devastated an entire generation, including many of the artists whose work is included in this exhibition. Echoing the apathy and homophobia of the Reagan and Bush administrations, the mainstream art world was initially slow to respond to the crisis, even as many artists were sick and dying. Working within and alongside activist organizations, including Gay Men’s Health Crisis, ACT UP, and Blood Sisters, artists raised public awareness about HIV/AIDS through propaganda campaigns and public interventions, yielding some of the most iconic images and slogans of 1980s queer rebellion—including SILENCE=DEATH. Drawing on the legacy of militant protest and coalition-building that flourished during and after the Stonewall Uprising, the artist-activists of the 1980s revived the struggle for social equality, justice, and queer lives—a struggle that still continues today.

WE’RE HERE!

In the late 1980s, at any LGBTQ march, AIDS protest, or pride parade, one would inevitably hear the chant, “We’re here! We’re queer! Get used to it!” This unapologetic demand for acceptance was, and remains, aspirational. The works in the final section of Art after Stonewall declare the presence of queer people everywhere and assert the validity of their existence.

In the late 1980s, at any LGBTQ march, AIDS protest, or pride parade, one would inevitably hear the chant, “We’re here! We’re queer! Get used to it!” This unapologetic demand for acceptance was, and remains, aspirational. The works in the final section of Art after Stonewall declare the presence of queer people everywhere and assert the validity of their existence.

Even in moments of triumph and liberation, personal and collective feelings of shame, inadequacy, and melancholy linger. Prejudice and homophobia continue, and cannot be healed by one riot or even fifty years of struggle. As David Wojnarowicz’s Untitled (One Day, This Kid…) reminds us, from the moment we are born, our society inculcates shameful feelings within each of us, brutally enforcing the conditions of acceptable behavior. The power in this work is that Wojnarowicz’s statement can so easily be applied to all kinds of prejudice and oppression today. This kid is all of us.